On Vanity and Vainglory

Still more medieval vices for the modern world

Today most see vanity as, at worst, a venial sin. Vanity is girls posing seductively for likes and upvotes. Vainglory has been largely forgotten. What’s wrong, after all, with a burning desire to rise to the top and be the best? Yet for Evagrius Ponticus, κενοδοξία (kenodoxía), vainglory, was one of the Eight Evil Thoughts.

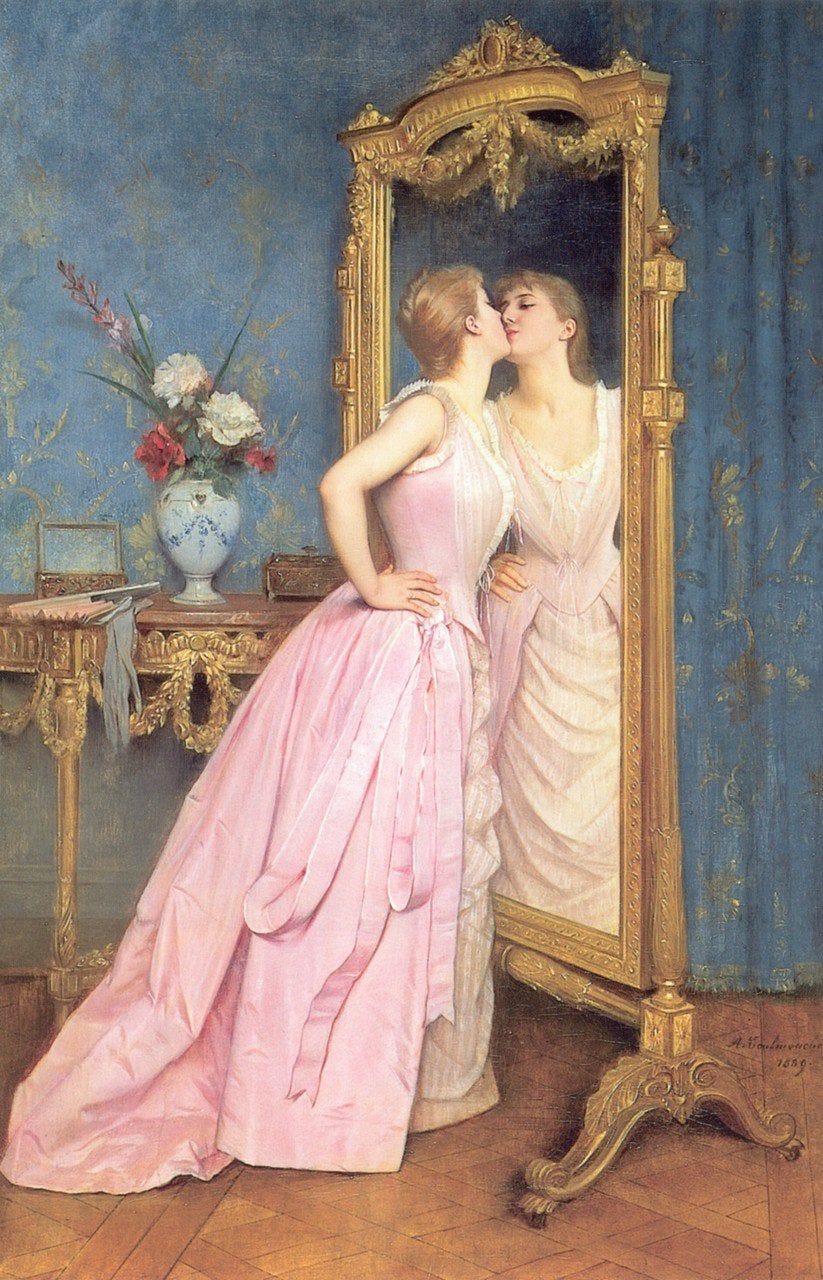

Just as Gregory the Great combined acedia and despair into Sloth, so too did he bring together superbia (pride) and vanagloria (lust for glory) into Pride. But while Gregory may have edited Evagrius, the Church remained keenly focused on vainglory. Preachers and authors of edifying discourses who warned that all beauty is fleeting and all glory transient.

Vanity is a desire to be seen as beautiful. The natural urge to look your best becomes an obsession with your beauty. Vainglory is a desire to be seen as better than your fellows. The natural desire to heroism is subverted into a desire to be seen as a hero. In both cases the focus shifts from “what can I do for the world” to “what does the world think of me?”

Both vanity and vainglory have their root in the Latin vanitas. Latin is Simple (for them, maybe) offers these English synonyms:

Emptiness

When we tie our identity to the things of this world, we attach ourselves to that emptiness that Hinduism calls maya or ignorance. As the Vedanta Society of Southern California explains:

Maya is the veil that covers our real nature and the real nature of the world around us. Maya is fundamentally inscrutable: we don’t know why it exists and we don’t know when it began. What we do know is that, like any form of ignorance, maya ceases to exist at the dawn of knowledge, the knowledge of our own divine nature.

To focus on the incidentals of your life is to become further entangled in maya. And maya can never fulfill your needs for meaning and purpose. Without that meaning and purpose, your life is empty and you have nothing better to do than while away the time on increasingly unsatisfying trivialities.

Untruthfulness

When you see yourself as a performer and the world as your stage, you are living a lie. You are not showing the world who you are, you are showing them what you think they want to see. You are creating a persona — the Smartest Man in the Room, the Richest Family on the Block, the Most Spiritual Person at your church.

If you spend enough time wearing a mask, you become that mask. But masks block your vision. When your world is built on an untruth, you must begin spinning increasingly desperate lies to yourself and others to keep your persona from being destroyed by truth.

As you invest more in your untruths and self-deceptions, your shaky castle of lies becomes your dungeon. Denying a hundred untruths is much harder than denying one. Your persona no longer fits and you no longer remember being anything else. All you can do is continue the role and wonder who you are.

Futility

Anas bin Malik reported: The Messenger of Allah, peace and blessings be upon him, said, “If the son of Adam had a valley full of gold, he would want to have two valleys. Nothing fills his mouth but the dust of the grave, yet Allah will relent to whoever repents to Him.”

Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī 6439, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 1048

As with most sins, vainglory can never be satiated. You can never be sexy enough, thin enough, smart enough, or rich enough so long as there’s someone out there who’s more endowed with those qualities than you. And that someone will always be there, especially the someone staring from the mirror reminding you of your failures.

Beauty fades, regimes change, and fortunes are lost. And even if you preserve your power, wealth, and good looks sooner or later you have to keep your appointment with the Reaper. Dawn goes down to day and nothing gold can stay. Maidens, warriors, scholars, and kings all must someday die.

Foolishness

For Evagrius Ponticus and Pope Gregory, vanity was foolishness because it took attention away from the Eternal and focused it instead on passing pleasures. They, like most Americans throughout our history, took for granted that there was an Eternal. There is no longer a consensus on that issue.

But even atheists can agree that vanity is based on untruth. To make oneself into an object of desire or fear is to become a role. You are pretty, you are tough, you are the founder of a startup — these are all things you have, not things you are. Things you have can be taken away, but what you are stays with you no matter how hard you try to escape it.

Vanity also leads to bad decisions. Those focused on youthful beauty ward off aging by plastic surgeries till they stumble into the Uncanny Valley of the Dolls. Vainglorious investors convinced they know the market better than anyone make catastrophic trades. You can reject the concept of Sin, but it’s hard to deny its consequences.

Empty Pride

Vanity and vainglory are both based in a love of a false self. As you identify more closely with that false self, you start believing your own hype. You no longer long to be successful, you now are successful. Those successes can puff up your pride and cement your conviction that you really are special.

This skews both your sense of self and of your world. You come to expect special treatment and are sorely wounded when the world refuses to acknowledge your genius. To walk away from the persona is unthinkable, so you declare skeptics to be peons and peasants who can’t understand you.

Ultimately you wind up Norma Desmond wandering around the empty mansion which is your self and declaring everyone else small. You may have nothing left, but still you have your Pride. And ultimately that will be taken from you as well.

Now that we have a better understanding of kenodoxía, let’s see what experts have to say on the subject.

Yet the word which cometh out of the mouth, and deeds known to men, bring with them a most dangerous temptation through the love of praise: which, to establish a certain excellency of our own, solicits and collects men's suffrages.

It tempts, even when it is reproved by myself in myself, on the very ground that it is reproved; and often glories more vainly of the very contempt of vain-glory; and so it is no longer contempt of vain-glory, whereof it glories; for it doth not contemn when it glorieth.

St. Augustine, Confessions, Chapter XXXVIII

St. Augustine’s Confessions has garnered fans from St. Thomas Aquinas to Ludwig Wittgenstein. It is the first Western autobiography and the first interior autobiography. Augustine’s reflections on his past life and his efforts to be free of his sins continue to shape theologists and psychologists.

As sinners go, Augustine was pretty run-of-the-mill. He stole pears from a neighbor. He spent a few years in the then-popular Manichean faith. He spent 13 years living with a Carthaginian woman who bore his child, then left her for an arranged marriage to a teenage heiress that fell through after Augustine decided to become a priest.

Most would view pre-conversion Augustine now as his fellow Northern African Romans viewed him — a bright young man with a teaching career and a concubine. (We might call her a long-term partner). We would find him a charming dinner companion whose head was perpetually up in the clouds, the sort of person we describe today as “spiritual.” If he seemed vaguely discontented with his life, that would hardly make him stand out amongst his fellow hipsters. Neither would his fascination with fringe religious movements.

After his conversion in 386, the bookish intellectual became a theological force to be reckoned with. For the next 44 years, Augustine would produce volumes of treatises and reams of correspondence. His de civitate Dei (City of God) served as a guide for the newly Christianized Roman Empire and would remain influential even as the Roman West crumbled. Much of modern Catholic liturgy, ritual, and theology owes a debt to St. Augustine’s philosophy.

In the section above, St. Augustine recognizes our innate need for praise. We are pack primates. Like our dogs, we want to be seen as good humans. But he also notices the ways in which our love for praise can turn against us. We can stay silent against evil for fear of being scorned. We can use flattery and smooth talk to gain the good will of the powerful. We can do the popular thing instead of the right thing.

St. Augustine also makes an interesting observation about those who “[glory] more vainly of the very contempt of vain-glory.” Spiritual self-righteousness is an ever-present danger for the devout. When you become proud of your spiritual accomplishments and righteous life, you shift your attention from God to your own spiritual achievements. Instead of forgiving your neighbor’s sins, you catalogue them as evidence that you are more faithful than them.

Vainglory can be loud, or it can be subtle. St. Augustine wanted to tear his vainglory out at the roots. You can perform heroic deeds and good works, but if your primary intention is to prop up your ego, you have fallen into vainglory. By fixing your attention on looking good rather than doing good, you have strayed from the path. Having been an enthusiastic participant in many of these sins, St. Augustine knew very well their allure.

The capital vices are enumerated in two ways.

For some reckon pride as one of their number:

and these do not place vainglory among the capital vices.

Gregory, however, reckons pride to be the queen of all the vices, and vainglory, which is the immediate offspring of pride, he reckons to be a capital vice: and not without reason.

St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa 2.2.132

After St. Augustine’s death and Rome’s Fall, the West was decidedly short of Christian philosophers. St. Thomas Aquinas was the last flowering of a 1,000-year Christian tradition that started with Origen. Building upon the Greek, Jewish and Arabic philosophy he learned under Albertus Magnus, Aquinas created a comprehensive theological and philosophical Church doctrine and in the process reintroduced Aristotle (whom he called “the Philosopher”) to the West.

You may notice I quote the jolly fat friar quite often. It can’t be helped. Catholic philosophy post-Aquinas has largely consisted of commentary on Aquinas. Post-Thomistic Catholic doctrine and discourse looks radically different after Aquinas. And then there are the secular scholars who took Aristotelian thought and used it to create an Enlightenment and a Scientific Revolution.

Thomas lived in a very stratified society where nobles were expected to dress according to their station. The king wore finery because he was the king. Warriors were still dying in defense of the Holy Land. Like the Philosopher before him, St, Thomas Aquinas recognized a golden mean between honest self-regard and sin.

A magnanimous man was great of soul and glory, what Aristotle called μεγαλοψυχία (megalopsychia). He knew his strengths and weaknesses because he had to. Warriors and statesmen faced constant competition. If they didn’t know their soft spots, their enemies would find them soon enough.

There was no shame in being a brave warrior for the Faith, nor in feeling a sense of accomplishment at your triumphs. But ultimately you knew that the glory belonged to God, and that your actions were glorious only insofar as you were acting in His service. As Aquinas put it:

To think so much of little things as to glory in them is itself opposed to magnanimity. Wherefore it is said of the magnanimous man that honor is of little account to him.

On like manner he thinks little of other things that are sought for honor's sake,

such as power and wealth.

Aquinas acknowledged that not every act of vainglory was a mortal sin. If you attained to your act of glory fairly, without serious offense against God or man, your vainglory is a venial sin, one that harms your relationship with God but does not cut you off from God’s sanctifying grace.

A venial sin becomes mortal when it causes you to turn away from God. When the acclaim of others become more important than God, you are in mortal sin. And as you fall deeper into vainglory, you’re likely to find yourself creating more sins and caring less about the spiritual consequences.

So how do we avoid these pitfalls? Aquinas quotes Jeremiah 23:24.

Let not the wise man glory in his wisdom,

and let not the strong man glory in his strength,

and let not the rich man glory in his riches.

But let him that glorieth glory in this,

that he understandeth and knoweth Me.

You can’t appreciate the temporal until you acknowledge the Eternal. You can’t understand the world until you acknowledge it doesn’t revolve around you. And you can’t find the things that matter until you stop chasing things that will make you popular. Ultimately, vanity is yearning need filling itself with an emptiness that will ultimately make it hollow.