The Moneylenders in the Temple

A brief history of modern usury

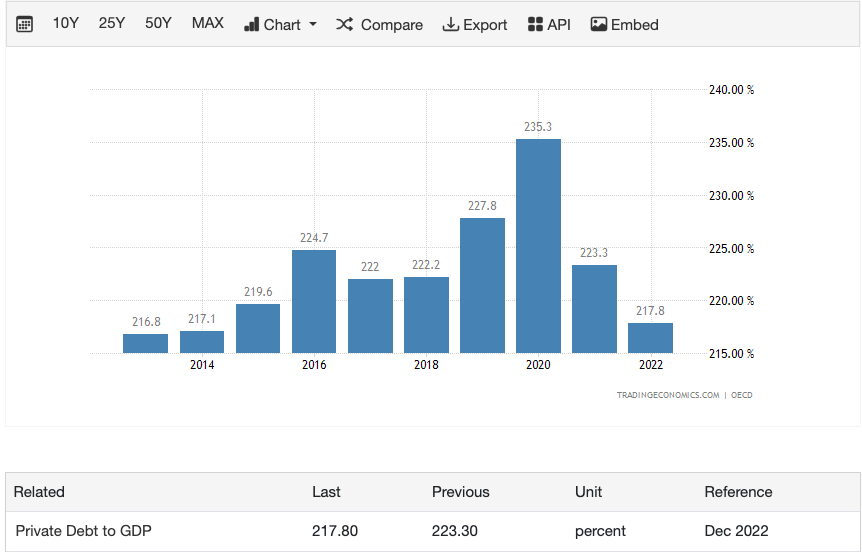

Modern America runs on credit. We take out mortgages to buy homes; we take out loans to buy cars and educations; we treat ourselves to expensive new toys and charge it to our credit cards. In 2022 US public debt (debts owed by federal, state, and local governments) amounted to nearly 120% of our GDP. Corporat…